Montana’s National Monuments: Preserving History, Landscape, and Culture

National Forests and Grasslands, State Trust land, National Parks – Montana is blessed with many types of public land. However, there is something special about our National Monuments. Like other public lands, National Monuments can protect habitat and ecosystems and give the public access to great places to hike, camp, hunt, bike, and other traditional public land uses. But it’s their unique focus on historic and cultural preservation that makes National Monuments such a special and important conservation tool. You can find no better example of what National Monuments offer communities than the three in Montana: Little Bighorn NM, Pompey’s Pillar NM, and Upper Missouri River Breaks NM.

An Act for the Preservation of American Antiquities (more commonly referred to as the Antiquities Act), enacted in 1906, was the United States’ first federal law recognizing the importance and value of the places and objects that represent the country’s history and prehistory. The act protected historical and archaeological sites and gave the President authority to establish national monuments to help protect and preserve these essential areas. The 59th U.S. Congress passed the act, and President Theodore Roosevelt signed it into law on June 8, 1906. The Antiquities Act today is used almost exclusively by presidents to set aside places as national monuments.

The Missouri River in the Upper Missouri River Breaks NM.

The Antiquities Act of 1906 is one of our nation’s most important conservation tools. Used to safeguard and preserve federal lands and cultural and historical sites for all Americans to enjoy. Since 1906, U.S. presidents from both parties have used their authority under the Antiquities Act to set aside land almost 300 times. Eighteen presidents have designated 150 national monuments under this authority.

In Montana, we’ve been lucky enough to have some of our most iconic and culturally important shared public lands protected in perpetuity as national monuments. We can enjoy these special places now and know that whether it is class trips or campouts, future generations will have the same opportunities to benefit from our National Monuments.

Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, designated by President Harry Truman in 1946

The first National Monument established in Montana is holy ground to many people. Little Bighorn Battlefield NM is the site of one of North America’s most famous battlefields, and it is the final resting place of many of the brave warriors and soldiers who fought in the epic clash.

Indian Memorial at Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument.

Located in southeastern Montana, along the ridges, bluffs, and ravines of the Little Bighorn River, the Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument memorializes the site of the Battle of the Little Bighorn, which took place on June 25-26, 1876, between the United States Seventh Cavalry Regiment led by Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer along with their Crow, and Arikara scouts, and the warriors of the Lakota Sioux, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho tribes led by Sitting Bull. The Battle of the Little Bighorn has come to exemplify the friction of two considerably different cultures: the buffalo/horse culture of the northern plains tribes and the highly industrial based culture of the United States.

The battlefield and landscape are well-preserved, and walking along Battle Ridge, it’s easy to look down in the valley and imagine the vast village of teepees along the river, to see warriors on horseback boiling up from the brushy draws. The land teaches in a way that books cannot, and it’s no wonder that generations of Montana school children have visited Little Bighorn, and why it attracts families from across the country.

Markers where soldiers and warriors fell are all over the monument.

Little Bighorn NM lies within the Crow Indian Reservation and plays an important role in the life of the tribe. Nearly every summer Native horsemen fill the valley in a breath-taking reenactment of the battle, and nearby Pow-Pows and parades celebrate Native culture.

This battle of Little Bighorn was not an isolated incident but part of a much larger campaign devised to force the surrender of the non reservation Lakota and Cheyenne. The battle was a short-lived victory for the Lakota and Cheyenne, as the death of Custer and his troops became a uniting point for the United States to increase their efforts to force native peoples onto reservations. The Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument was originally named Custer Battlefield National Monument, designated by President Truman in 1946. President George H.W. Bush renamed the site on December 10, 1991.

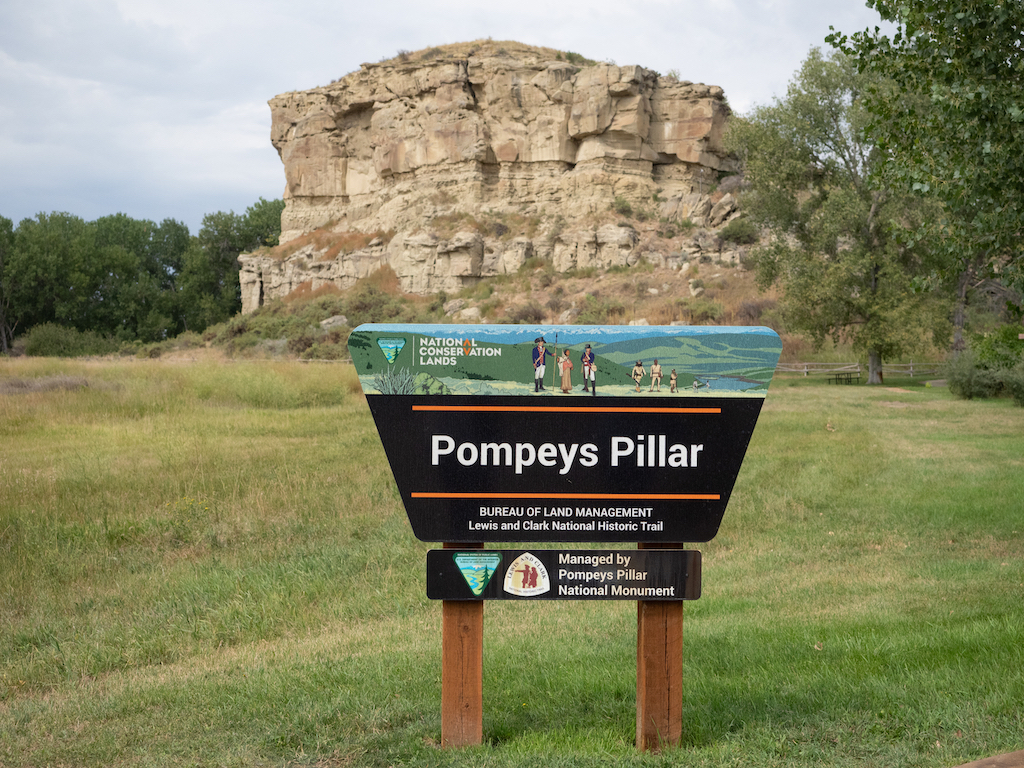

Pompey’s Pillar, Designated by President Clinton in 2001

Our smallest National Monument is a striking sandstone outcrop looming over the Yellowstone River. It’s also a signpost, a lookout, and one incredible collection of graffiti.

Pompeys Pillar, a sandstone formation and 10.000-year old tablet.

Pompey’s Pillar National Monument covers 51 acres on the banks of the Yellowstone River, all around its namesake Monolith, a massive sandstone outcrop covering about 2 acres at its base and rising 120 feet. It’s impressive to see, but look closer and you’ll start to understand why it’s a National Monument. The tower has been an important site to the people who live here going back over 11 thousand years, and history is written on its walls.

Why this rock is so special has a lot to do with location. The monument’s prime location at a natural ford in the Yellowstone River, and its geologic distinction as the only significant sandstone formation in the area, have made Pompeys Pillar a celebrated landmark and unique observation point for many, many people for at least 11 thousand years. Hundreds of markings, petroglyphs, and inscriptions have transformed this geologic phenomenon into a living journal of the history of the American West.

Signs of those who’ve come before at Pompey’s Pillar.

The Pillar was used for centuries as a preferred campsite by the Crow Tribe and other Native peoples as they traveled through the area on trading, hunting, war, or other expeditions. Archaeological and ethnographic evidence suggest that the Pillar was also a place of religious and ritual activity. Throughout the 19th century, early settlers, fur trappers, railroad workers, and military expeditions used the sandstone to register their passing.

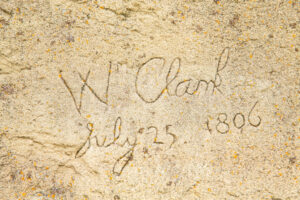

Carved signature of William Clark, Lewis and Clark Trail, Pompeys Pillar National Monument, Montana.

Most people probably know the tower from one prominent visitor, the one who named it and left his own calling card. Captain William Clark of the Lewis and Clark Expedition named the Pillar “Pompy’s Tower” in honor of Sacagawea’s son Jean Baptiste Charbonneau, whom he had nicknamed “Pomp.” Nicholas Biddle, the first editor of Lewis and Clark’s journals, changed the name to “Pompeys Pillar.” Pompey’s Pillar bears the only remaining physical evidence of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with William Clark carving his name and the date, July 25, 1806, on the face of the butte. Both the sandstone and Clark’s signature appear the same as they did over 200 years ago.

Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument, designated by President Bill Clinton in 2001

When a lot of Montanans talk about “the Breaks,” they get a dreamy look in their eyes. To some, the Breaks means a wall-tent hunting camp and big mule deer bucks. Others know and love the Breaks as one of the state’s premier boating destinations, with hundreds of miles of water to explore and terrific fishing. History buffs make pilgrimage to the Breaks because to them it’s maybe the best spot on the Lewis and Clark trail to see the river through the eyes of the explorers. It’s a place where you can launch a canoe and paddle and camp for days through an area that is largely unchanged in the 200 years since the expedition.

The Missouri flowing how Lewis and Clark saw it.

This wild region of canyons, coullees, buttes, and steep bluffs is one of the most uniquely beautiful parts of the state, and the Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument contains many interesting biological, geological, and historical objects. From the Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge to Fort Benton, the monument traverses 149 miles of the Upper Missouri River, the neighboring Breaks country, and parts of Arrow Creek, Antelope Creek, and the Judith River.

The monument includes the Fort Benton National Historic Landmark, parts of the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail and the Nez Perce National Historic Trail, the Cow Creek Area of Critical Environmental Concern, the Missouri Breaks Back Country Byway, six wilderness study areas, and a watchable wildlife area. The entire region was the homeland and lifeblood of Tribal Nations; the river served as the route for the Lewis and Clark Expedition, then the waterway for steamboats, and an attraction for traders and fur trappers. Later, the river and the Missouri Breaks were havens for desperados trying to stay a step ahead of the law. The land was also a source of hope and inspiration for several generations of Montana homesteaders.

Canoeists on Missouri River near Judith Landing, Upper Missouri Breaks National Monument, Montana

Ranchers still make a living grazing cattle in the region, and the landscapes are right out of a Charles M. Russell painting. It’s a tough-looking country but great habitat, and the Breaks is home to over 60 species of mammals, dozens of species of birds, amphibians, fish, and reptiles. Many pressured species thrive in the Monument, including sage grouse, burrowing owls, soft shelled turtles, the rare shovel-nosed sturgeon, and one of the last remaining populations of wild paddlefish. It’s terrific elk and mule deer country and a favorite destination of the state’s big game hunters. It’s an upland bird hunter’s dream, with plenty of room to follow dogs after sharptail grouse, Hungarian partridge, and pheasants.

National Monuments, Key Part of Public Land System

With Montanans finding so many opportunities to enjoy and benefit from these National Monuments, it’s no wonder they have broad popularity. According to a recent Colorado College poll, 82 percent of Montanans support presidents continuing to use their ability to designate existing public lands as national monuments to maintain public access and protect the land and wildlife for future generations. It also showed that 78 percent of Montanans support creating new national monuments to protect historic sites or areas of outdoor recreation.

Montana is loaded with cultural and historical sites that offer boundless recreational opportunities and are core to the story of our lands and the people who have moved across them for generations. As Montana grows and changes rapidly, it’s critical we continue to preserve these special places. We can use our nation’s shared, great lands to not only celebrate and draw inspiration from our past but also to learn from it so we can create a better tomorrow. The President needs to be able to protect valuable resources on federal lands from potential threats. The Antiquities Act can and should be utilized to preserve resources for future generations.